Mania Coming of Age

During nearly the entire 17th Century, the Netherlands enjoyed its historian-dubbed Golden Age, within which was the forever-remembered “tulip mania” episode in 1637. Twenty-first Century familiarity with the history of that tulip buying-panic is typically sourced from a popular, still-in-print 1841 book: Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds by Charles Mackay (Amazon, $12.95).

Modern author, Anne Goldgar’s 2007 book Tulipmania, Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age tells us that in early to mid-1600s Netherlands, the Dutch enjoyed a republic that had a uniquely prosperous economy compared to its counterparts in the rest of Europe. Dutch society became dominated by prosperous oligarchies of wealthy merchants who chose not to make themselves into an aristocracy.

The Dutch economy, says Goldgar, was a sort-of economic beacon that offered high wages and, hence, it was an economic magnet that attracted a gaggle of immigrant-labor from surrounding regions. [Hmmm.] Its northern ports, particularly Amsterdam, were the international trading posts of Europe. In brief, the Netherlands’ trading prowess vaulted it into becoming Europe’s seat of economic sophistication.

Indeed, Amsterdam became the world’s center of cosmopolitan culture that included artists who produced some of the most continuously renowned and beloved paintings from then until now…. Rembrandt, Vermeer, van Ruysdael, Franz Hals, to name a few Dutch painters of that era. Amsterdam’s 1885 Riiksmuseum (recently overhauled) houses a breathtaking collection of them. Here is one of its galleries.

“Tulipmania would probably not have happened”, says Goldgar, “in a society less commercially developed than the Netherlands. But in this case money intersected with aesthetics. As luxury objects, tulips fit well into a culture of both abundant capital and a new cosmopolitanism.”

Tulipmania’s important commercial context: The early 1600s Netherlands’ inventive and resourceful business acumen spawned the creation of international business growth-tools such as an insurance company in 1598, a public exchange bank in 1609 and a lending bank in 1614. There was also another start-up, in 1618, of interest to us in this paper: a commodities exchange.

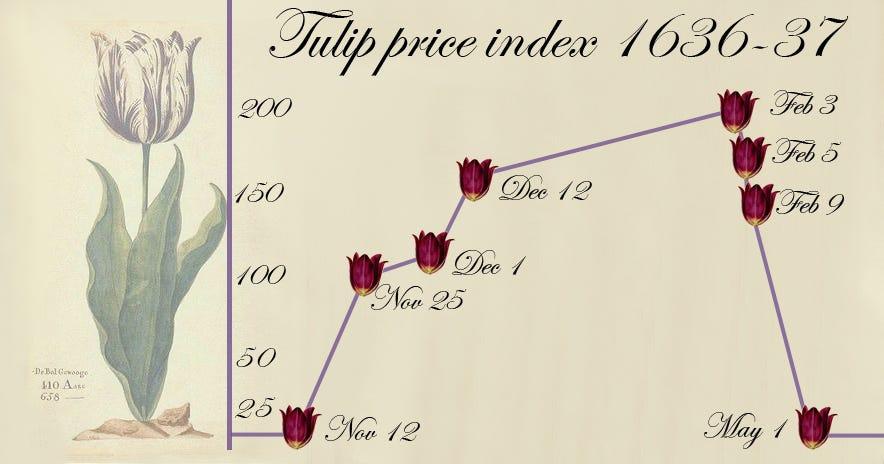

During the historical eye-blink between November 1636 and early February ’37, thousands of routinely calm, hardworking Dutch citizens were literally caught up in a frenzy of buying and selling tulip bulbs. Probably few were actually selling, other than to re-deploy the proceeds into other bulbs deemed to be more attractive investments. Exchange prices of the more precious tulip bulbs soared 10X. Then, just as suddenly and without an apparent trigger, bulb prices crashed; by May 1637, they had fallen back to their unexcited values of six months earlier.

During the mania, rare bulbs had changed hands at ballooning prices; indeed, some single bulbs peaked at values greater than the cost of a house. It was apparently the first futures market in history, and like so many that would follow, it crashed, which turned sharp-eyed wizards that were both speculators and “investors” into overnight fools. The Amsterdam commodities exchange collapsed and quickly just disbanded. It is easy to imagine that there were Warren Buffetts and Charlie Mungers of that day publicly tsk-tsk-ing on the sidelines.

Manic Then and Now

The manic-behavior history lesson is far from forgotten today, as proven by the fact that MacKay’s seminal, 182-year-old book remains in demand. A mere 30 years (a single generation) ago…. decades after the US’s landing of men on the moon…. the technology mushroom known as the “information superhighway” broke into widespread availability and adoption in the early 1990s. As if it were a wildfire, it raced into bettering our daily lives and eventually the lives of all human civilization; it created profound improvements to business efficiency and it was marvelously without government financial assistance.

Thus, in early 1999, the Internet technology-dominated NASDAQ stock index suddenly entered a “dot-com” mania period. The mania that evolved was essentially about fresh, young companies, begun at a proverbial kitchen table, or home garage and named xxx.com; they went to market with net operating losses presumed to be normal and appropriate for such attractive “investment opportunities”. The majority of dot-coms were software companies. They shared one characteristic that would give birth to thousands of under-age-30 creators who instantly became multi-millionaires: scalability. Their scale was essentially unlimited; it was made instantly possible based on a new-style product anomaly: it was sold and delivered to customers via the Internet, for a modest price. The anomaly was that the products’ fully loaded cost wasn’t burdened by traditionally significant overheads, including: piece-by-piece labor, packaging, shipping, brokering, travel, meetings, salespeople, and inventory.

Demand and prices for dot-com stocks soared into the late 1990s. As it always does, Wall Street’s scale-up mongers responded by rapidly and substantially increasing the supply. Dot-com companies typically went on the market with few fundamental investment characteristics. Instead, they were sought after for their presumed sales growth ad infinitum. Prominent among them was a new on-line-only retailer called Amazon, which re-defined “market share”, because it did not price its goods to make a net profit. Indeed, after more than 5 years, Amazon’s total accumulated net income was almost nothing. For undaunted 1999 stock buyers, their demand was insatiable. It overwhelmed Wall Street’s enhanced 24/7 supply resources. It was a true stock buying panic. Despite its intensity, however, dot-com mania lasted less than 2 years.

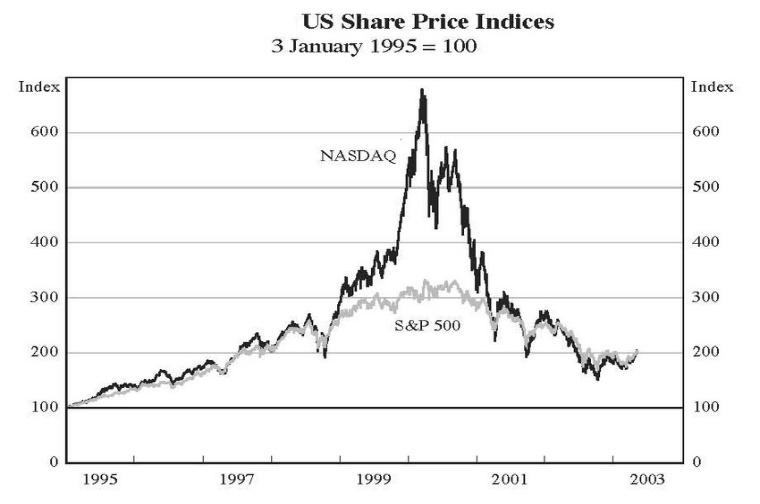

This NASDAQ chart forms a picture of the briefly outsized pricing of dot-com stocks in 1999/2000. It demonstrates how they became, for a while, commodity-priced (as we said at the time). A fundamental formula that applies on top of a commodity’s cost is:

Price = Supply X Demand

and, because fundamentals (earnings, etc.) are not present in a large group of start-up companies, this formula and the graphic comparison to the S&P 500 above display the dot-com group’s apparent “mania value”.

The 2023 Seven-Stock Surge – mania, or not?

The arbitrary 12-month period we have now just ended neatly frames a performance anomaly delivered by 7 of the largest market cap stocks in the S&P 500 Index.

| 2023 gain | |

| Apple | 48.2% |

| Microsoft | 56.8% |

| Alphabet | 58.3% |

| Amazon | 80.9% |

| Nvidia | 238.9% |

| Meta Platforms | 194.1% |

| Tesla | 101.7% |

| S&P 500 | 24.2% (top 7 in the index = almost 30% weighting) |

In addition, the market’s return was broad-based. The year 2023 floated nearly all boats, as shown in the S&P 500’s Advance/Decline line [daily measure of the number of stocks rising minus the number falling].

Thus, while nearly all types of common stock investors likely had a “good year” in 2023, very few in the portfolio management business would ever be positioned to ride one sector into a spike such as this year’s technology stocks, driven by manic buying that evolved into “fear-of-missing-out” behavior.

The New New Mania

So, why have we discussed ancient and modern mania here?

There is Bitcoin and its hundreds of crypto currency blockchain brethren that have seen multi-thousand percent fluctuations in their dollar values during their 6-to-10-year availability. In 2023, the crypto-currency leader Bitcoin, supported by several important technical factors, rose in dollar-price by 154%. In January 2024, it has continued to shoot upward, as the SEC will apparently soon permit major US investment houses to offer crypto-Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs); this is important, because the backbone of each crypto is its maximum possible number of coins that can ever exist.

Within the past twelve months or so, the US and the world have developed what appears to be a full-fledged mania over the flowering of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and how to invest in its sudden societal surge into worldwide business, education, even governments and charities. AI is not your everyday mania. AI is: (a) not very new (several iterations since the advent of computing), (b) not an investing category, and (c) not a product. Similar to the Internet itself, AI is a technological tool. But the tool carries a capability-threat that opens fearful portals, according to many of those most knowledgeable. One of its practitioners, Elon Musk, has said he believes AI is so potent that it might disrupt worldwide societal order unless its implementation speed is tempered (by whom, and under whose rules he did not say). As we write, US FBI Director Chris Wray speaks about the massive US security threat of China’s highly focused cyber-intelligence hacking community which, he avers, is at least several times greater than US capability. Wray did not introduce the AI element into that grim picture, but we can presume.

AI Investing: Although AI will likely and quickly revolutionize the functional elements of most industries and endeavors, we will focus here on the investment community’s apparent intent to use the tool for “favorable” active portfolio performance management. We use quote marks to emphasize the long-sought target of active portfolio managers: to exceed their benchmark’s performance, typically with the same, or reduced level of risk.

The portfolio management community expects that AI can and will guide its managers to execute trades that represent a leg-up, i.e., enlightened and timed trades enhanced by a thousand-fold plethora of tiny market and societal inputs that can, within seconds, be sensed, captured, aggregated and converted into market-beating equity transactions.

But this writer believes that that current expectations for AI-enhanced results are constrained by a simple macro weakness….. We might call it the AI club’s Uniform Outcomes Syndrome. In brief: if a portfolio manager is one among many AI users, members of that club have little, or no chance to outperform. If the AI user-club has a sufficiently large membership (and why would it not be huge?), then the club’s members ARE the market and cannot therefore hope to beat themselves….. unless humans override the sameness of AI output (in which case, AI will turn out to be just another variety of quantitative analysis). Moreover, it seems that a manager’s opportunity to manipulate portfolio risk exposure within an AI regime will be quite limited.

Expected Impact: Although AI might enhance all portfolios’ performance, AI-tuned “active” management will likely become an oxymoron and its fees must be reduced to a level close to that of passive index fund managers.

The Future: A Dream for AI?

In all of recorded human societal history, wars and rumors of them have remained a literal constant. The alleged and actual reasons for war rarely came close to justifying the ensuing level of suffering, death, damage and debt they left behind. In fact, the triggers for war-waging activities often appear to be largely irrational (e.g., the “domino theory” in Vietnam, the alleged “weapons of mass destruction” in Iraq). If that is true, can we consider that Artificial Intelligence may hold the potential to help manage-down the world’s most disastrously consequential human actions, and reactions that occur within the war departments of governments (and even among organized terrorists)?

In summary, mania has been, and likely always will be, lurking in the wings of investing, because mania is a by-product of the trait we all hate to realize and admit is built into our DNA: Greed. It causes otherwise smart, logical, methodical people to become caught up in a siren’s song that presents itself as an irresistible “opportunity” that is rich on assumptions, but weak on evidence. Well established portfolio managers will look to fundamentals and therefore shun participation in high-risk manias that appear from time to time.

VERITAS….

The TRUTH is absolute.

But perceptions and expressions of it are typically dependent variables.

HAPPY NEW YEAR