US Government Debt Default Doomsday (DDD) Was Over-Hyped

There is adequate federal cash flow to service its Treasury bills, notes and bonds…for some period of time.

Doomsday: US Treasury Secretary Yellen announced a June 5, 2023, deadline for the US’s continued ability to pay its bills. This was made-for-TV news, replete with a continuously ticking countdown clock in the corner of the screen. Viewers were urged (by all members of Congress) to believe that, on that date, the US Government would inform US and foreign holders of currently maturing Treasury bills, notes and bonds, and holders with interest payments due on them, that the payments would not be made on time. That notice, if it happened, would completely fulfill the definition of the doomsday, no-no event: Default.

Avoidance of debt default is and must be the highest priority in any government’s spending, because the consequence would be a severely curtailed future ability to borrow, and then only at a much higher interest cost [see once-rich Argentina…9 defaults in history causing triple-digit inflation and a 2023 debt-swap maneuver that Fitch classifies as imminent threat of default].

Congressionally adopted annual budgets authorize, but do not mandate, specific “discretionary” spending. Day-to-day matching of cash on hand to disbursements is always a Treasury Department function

In January, Treasury Secretary Yellen began making dire public pronouncements and sent hard-nosed letters to House Speaker McCarthy and other key Congresspeople. In her view, worldwide financial interests would view any failure to pay 100% of all its bills…on time…would be a “default”. She became increasingly strident and, in mid-May, predicted to an association of community bankers that “A default would crack open the foundations upon which our financial system is built.” This time, she did not mention what a default’s impact would be on the US Dollar’s reserve-status hegemony.

Non-Doomsday (and not the first time): The US 2023 doomsday would indeed have caused some federal bill-paying to be deferred; and, worst case, some departmental payrolls might have to be temporarily trimmed, via hours-worked curtailments, or layoffs of “non-essential personnel” (see 1995 and 1996 federal shutdowns1). But in 2023, Congresspeople uniformly committed to confronting the realities of a no-new-borrowings Treasury cash flow squeeze. On the other hand, if the June 5th doomsday had been triggered, Congress’s constituents back home would have recognized a cash flow shortfall when they saw it; it would have looked eerily like their family’s cash-priority setting sessions around the kitchen table. Mortgage payments, groceries and car payments always get done ahead of credit cards usage for dining out, movies and vacation trips. That said, Congresspeople know that those back-home voters have no tolerance for their government being ham-handedly operated as an on-purpose train wreck created over ideological clashes.

Had there been no debt-ceiling resolution by June 5th, Congress wouldn’t have had to get its hands dirty in the non-doomsday priority-setting exercise. The Treasury is responsible for doing that, without legislation. Congressionally adopted annual budgets authorize, but do not mandate specific “discretionary” spending. Day-to-day matching of cash on hand to disbursements is always a Treasury Department function. (Example: Congress’s 2020-21 fiscal year budget authorized a vast amount of Covid-relief spending that, as of now, remains unfunded and unspent.)

Absent a debt ceiling expansion, The Great 2023 Budget Allocation process might have looked like this sort of work-around….

Priority #1: Full servicing of existing debt; full payment of interest, when due, and refinancing of all maturing debt issues. (Debt replacement does not count against the debt ceiling.)

Priority #2: Full, timely payment of all entitlement benefits (Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, etc.)

Priority #3: Full funding of currently budgeted defense department allocation.

Etc, etc., down to lower urgency priorities that could either be deferred, or operate on partial funding, for a time.

Shrinking names for exploding numbers

So the expansion of continuous, very intentional spending in excess of cash collections will apparently continue to run with gusto in future budget years and the nation’s debt will continue to grow without real limits. This process taxes the human capacity to imagine it…so we use small, simple numbers, i.e., $1.5, or $31.4, to express the annual deficits and accumulated US Government debt in trillions. But we submit that no one, not Congresspeople, not even Secretary Yellen, can actually grasp numbers that have twelve zeros behind them. We can know one thing that is neither subjective nor political: NOT ONE DOLLAR OF THE US’s ACCUMULATED 12-ZERO NATIONAL DEBT WILL EVER BE RETIRED, unless (imagine this) Congress actually produces a string of robust annual budget surpluses and then continuously operates with no more than modest expansions of the debt burden.

FYI: The next bracket of US Government accumulated debt will be measured in innocuous-looking single-digit numbers of quadrillions… i.e., fifteen zeros.

Measuring absolutes and relatives

Instead, the most likely scenario will be continuous future inflation via dollar de-valuation (NOT Fed policy) that is well beyond the Fed’s much be-labored 2% inflation-rate target (since 2012). Such devaluation will shrink the value of the government’s (and everyone else’s) debt2 without paying it off, which makes a re-financing “cheap” using de-valued dollars. The insidious impact of dollar-devaluation will automatically grow the economy’s nominal amount of total goods and services being generated which creates make-believe shrinkage in the US Government’s debt-to-GDP growth.

[Aside: We have always thought that GDP should be measured in terms of widgets produced and hours worked. That approach would arrive at non-squishy GDP growth numbers, independent from the declining purchasing power of its fiat currency …and it would deliver a reliable economic efficiency measurement to boot.]

Sustainment

Is substantial debt-growth by the world’s largest fiat currency issuer an un-ending spiral? Well, yes, because it actually works…until it doesn’t. And that is because the iron-clad underpinning of the entire debt/inflation/GDP expansion system is its participants’ ongoing, unquestioning trust and belief in its stability. However, please review 2008 for a US and worldwide glimpse of how system-trust can implode, by surprise, inside a few days [think Lehman Bros. and Bear Stearns].

We couldn’t have said it better than this: Cornell University professor Eswar Prasad, author of The Future of Money tells us: “It is becoming harder to view the US as a well-functioning, dynamic economy with a deep and sound financial system, backed up by a robust policymaking process with checks and balances.”

In a different context, we might ask: What happens when the next war is sprung and the US tries to control the worldwide impact of pursuing it using dollar-based economic sanctions? The money-cost of war has always been substantial, but beginning four US wars ago, in Vietnam, US war expenses were no longer linked to gold and hence dollars could be created, as needed, without limit.

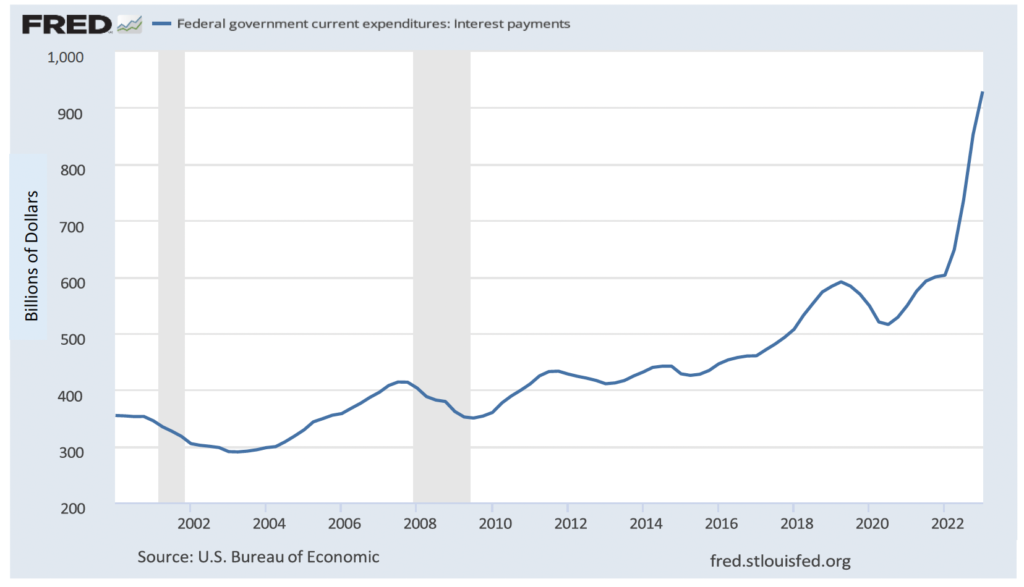

The Fed’s 21x interest rate bumps during barely more than one year have already recast finances.

Without regard to the amount of future US Government debt growth, its interest cost burden is already ballooning. We view the Federal Reserve’s interest rate boosts a bit differently from the financial press. We see increases/decreases in the Fed’s progressive interest rate prescriptions as proportionate, not lineal. For example, in March last year, the Fed funds rate was finally kicked from its warm, near-0% nest. Three months later it soared from 1.75% to 2.50%. In our view, that move was not a mere ¾% increase; it was a 43% increase…in one month! Thus far, the Fed’s entire 1¼-year-old rate bumping regime has gone from a super stimulating 0.25% perch to 5.25% (a 21x multiple) which is apparently going two bumps higher this year.

It’s been a long interval during which the US Treasury and the rest of us have been borrowing money at rock-bottom interest rates. Reminder: 15-year fixed rate home mortgages were still available at 2% a mere 19 months ago. Since 2009, which is a business lifetime for big borrowers…real estate developers, manufacturing companies that are building expansion plants and venture managers have happily wallowed for more than a decade in super low-cost borrowings which re-defined the term “leverage”.

No leverage here

Not all debt-financing is done to magnify the return on invested money, plus a money-rental fee (interest). For most of the past 14 years, the biggest borrower of them all…the US Treasury…was at first faced with the aftermath of the 2008 Financial Crisis which panicked the Congress into staggering annual budget deficits that in turn produced steep new Treasury borrowings and caused the Fed to flush borrowing rates almost out of existence. Twelve years on, the 2020 Covid-19 Panic stimulated the Congress to literally create and distribute trillions of new dollars which drove the US Treasury debt-to-GDP curve almost straight up (see the chart in our April issue). Unlike investments, there was no realistic avenue for the US Government to recover its stimulus-dollars, as it had hoped to do when it kept Chrysler and General Motors afloat in 2008. (It didn’t recover: the Treasury reported that it eventually lost $9.3 billion on its US-based automotive equities, but it was quick to muse and suppose that the number of jobs it had “saved” had amounted to leverage in the economy.)

Interest matters

Near the end of the Covid era, Congress took on a major mission expansion that requires even bolder debt-financed spending for climate reaction. This recently fortified political movement involves US Government funding of newly created long-term debt that is invested in the equity of particular (mostly start-up) companies which are striving to produce goods designed to drive down US production of atmospheric carbon…and to replace those goods with non-carbon substitutes. The goals are very long term, 20 to 30 years. Hence, it follows that the related debt already incurred will exist for a very long term (but, during that long goal period, it won’t be avoiding the cost of re-financing at triple/quadruple the interest rate it was paying just one year ago). Take a look here at how the Fed’s interest jackings are already blowing out the “maintenance cost” of our much discussed $31 trillion ($31,000 billion) bowl of existing debt.

Together with stout 21st Century annual federal budget deficits that are now generally expected and accepted, this created-since-2008 debt ganglia has never before been burdened by serious interest payments. So, here we are, staring up at the Federal Reserve-created soaring interest cost of our recently juiced government debt which, if it hasn’t boggled us yet, will surely re-define boggling, during the next five years.

Commercial real estate faces tough conditions

Commercial real estate investing has uniquely important aspects that make it both attractive and risky. The main risk is its illiquidity. The other risk is its major, intermediate term debt burden. Because commercial real estate typically involves a very large capital commitment, its investment naturally requires leverage, via mortgage debt. The commercial market, mostly urban office rental properties, hotels (overnight rentals) and medical buildings, is typically operated with a significant amount of 5- to 8-year debt that is usually re-financed at maturity. The size of the US commercial loan market is now $4.5 trillion, according to Cohen & Steers and the Mortgage Bankers Association. About 45% of all commercial RE loans are held by banks, while 55% are in the hands of non-bank lenders. Notably, C&S also reports that 15% of office loans already have inadequate cash flow.

Entire local markets in a number of large high-cost cities have experienced a significant loss of businesses, including a large number of headquarters businesses, during and after the Covid era. They moved away, mostly to non-state-income-tax locations in Texas, Florida and Tennessee. In addition, those same population-loss cities have seen a major evacuation of office workers to their work-from-home mode which has become permanent by choice. Already, some large properties in New York City and others have announced major re-structuring of office buildings to convert to luxury hotel/residential use.

Although large, nationwide banks today have a low exposure to commercial real estate loans, quite the opposite is true of the mid-size banking sector. This aspect, on top of sudden mid-size bank failures, is almost surely keeping federal regulators and US Treasury anticipators quite busy.

1 Between 1995 and 1996, the US government endured two partial shutdowns during the presidential term of Bill Clinton, who had adamantly opposed appropriation bills for 1996 by congressional Republicans (who had a majority in both chambers) and House Speaker Newt Gingrich. But then Clinton and Gingrich went on to jointly develop and enact budget surpluses in 1998, 99, 2000 and 01. But, even with four successive surpluses, there was only Congressional discussion of paying down the federal debt.

2 For decades, US homeowners have made a science of this debt-devaluation syndrome: Buy a home; wait for its value to inflate 5-7 years; sell the inflated-value home and pay the devalued fixed rate mortgage balance; buy an inflated new home…. etc. Many Americans’ personal net worth is significantly tied up in the net value of their home. As with the federal government, this syndrome worked for homeowners, furiously, until it didn’t…in 2008/9.

Commentary

Commentary was prepared for clients and prospective clients of FiduciaryVest LLC. It may not be suitable for others, and should not be disseminated without written permission. FiduciaryVest does not make any representation or warranties as to the accuracy or merit of the discussion, analysis, or opinions contained in commentaries as a basis for investment decision making. Any comments or general market related observations are based on information available at the time of writing, are for informational purposes only, are not intended as individual or specific advice, may not represent the opinions of the entire firm and should not be relied upon as a basis for making investment decisions.

All information contained herein is believed to be correct, though complete accuracy cannot be guaranteed. This information is subject to change without notice as market conditions change, will not be updated for subsequent events or changes in facts or opinion, and is not intended to predict the performance of any manager, individual security, currency, market sector, or portfolio.

This information may concur or may conflict with activities of any clients’ underlying portfolio managers or with actions taken by individual clients or clients collectively of FiduciaryVest for a variety of reasons, including but not limited to differences between and among their investment objectives. Investors are advised to consult with their investment professional about their specific financial needs and goals before making any investment decisions.

Investment Risk

FiduciaryVest does not represent, warrant, or imply that the services or methods of analysis employed can or will predict future results, successfully identify market tops or bottoms, or insulate client portfolios from losses due to market corrections or declines. Investment risks involve but are not limited to the following: systematic risk, interest rate risk, inflation risk, currency risk, liquidity risk, geopolitical risk, management risk, and credit risk. In addition to general risks associated with investing, certain products also pose additional risks. This and other important information is contained in the product prospectus or offering materials.