The Fed’s All-In Bet

Market Commentary November 2020

THE ECONOMY, IN A NUTSHELL: In normal times, a market economy makes and sells goods and services, produced by millions of people earning paychecks which they spend and invest; meanwhile, the territorial government collects a share of the commercial volume, in order to provide communal services and pay for collective defense. For a long number of years, the US government’s cut has been increasingly insufficient to pay for the size and scope of its proliferating list of services.

THE 21ST CENTURY: During the 20 years of this century in the US, there has been a stream of national pestilences: (1) distant, very expensive wars without end and without supplemental funding of them, (2) two chronic economic recessions, plus (3) a third recession, encased in a super-rare pandemic, for which no effective treatment protocol, or vaccine yet exists and (4) a 2020 wave of deeply festering online social crudeness that resembles the functions of a movie theatre’s popcorn machine.

THE 2020 SHOW-STOPPER: All of the above have been absorbed into an increasingly non-functioning, two-party political system that no longer cares to discover compromise; in fact, it openly loathes such “weakness”. This year, spooked by a pandemic-driven economic collapse, the two parties did set aside endless political wars long enough to hammer out and adopt $2 trillion of immediate cash distribution schemes that would put money in individual and small business pockets, for a limited while. The Congress, in bi-partisan haste, ballooned the US Treasury’s budgeted 2020 $1 trillion deficit to more than $3 trillion (that’s $3 thousand billion)…. and the US stock market immediately blossomed on that news; it began to bathe in that tub of warm Treasury-milk, staging a quick, V-shaped crash-and-recovery, especially among “technology stocks” (i.e., capital-efficient companies) that actually rang-up sales growth, amid the sudden recession, because of (not in spite of) their customers’ home imprisonment.

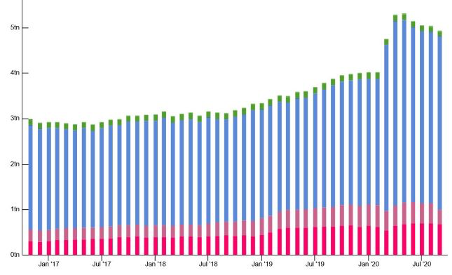

ENTER, THE FED (and its global counterparts) The Federal Reserve is now and, for 20 years, has been the US Government’s fixer of Ballooning Annual Deficits [BADs]. Not since the waning years of the 20th Century have federal budgets come close to break-even. Consequently, the BADs have been funded by a Burgeoning Bundle of Debt [BBD], issued by the US Treasury which the Fed immediately gobbles up as an investment. Within 2020, the Fed investment portfolio has increased from $4 trillion last year, to more than $7 trillion…. And it’s still on the way up. Note: The Fed’s initial long-term portfolio climbed to $4 trillion in the 2008 recession. Before that, it traditionally held less than $1 trillion of 91-day US Treasury bills.

Much to the Fed’s disappointment and chagrin, inflation all but disappeared. It’s a problem, they say. Based on thinly explained reasons developed in the past ten years, it is now the Fed’s policy to actively promote and provoke a 2% annual inflation rate (which will deliver almost 50% inflated consumer prices over 20 years). Despite inflation’s deleterious impact on people’s savings and bond investments, the Fed’s 2020 policy campaign is directly aimed at dis-advantaging investments in money market funds. (More below)

Twenty-first Century global interest rates have moved steadily downward to their current record low, at zero percent. Sub-zero interest rates have already been used in a number of countries and the Fed is known to have prepared for joining that crowd. After all, the government’s BBD interest payments are not ballooning, despite the doubling, then tripling of its principal size. The increasingly obese BBD is not being dragged along like a mobile home with flat tires. Instead, it floats on a deep, green lake of newborn money, fathered by the Fed and supplied by an artesian river of new dollars. (The Fed routinely proves that the created dollars are real, by using them to purchase real bonds and other investments that trade in open markets.) The post-2008 Fed policies are unprecedented and therefore untested and uncertain. Never has rapid, sustained money supply growth produced lower interest rates; in the past, the opposite not only happened, but it was entirely expected and logical. The Fed now touts its array of “tools” which are at the ready for thwarting recession. The tools list is long and lengthening. Among the 2020, first-time Fed investments are: (1) commercial paper, (2) municipal securities, (3) corporate bonds, including high yield “junk” paper and (4) consumer credit cards and automobile debt, and much more, in addition to its already massive home mortgage buying program (since 2009). Also, common stock investments are not ruled out. In summary, the Fed is now so deep in the market that it hired mega-manager BlackRock, Inc. to structure and execute most of its bond portfolio.

Fed Chairman Powell has now promised not only “…to use these powers forcefully, proactively and aggressively”, but he also assured us, “….when the time comes, we will put these emergency tools back in the toolbox.” Harrumph! we feel compelled to say. And then we must ask: What happened to the Fed’s 10-year-old promise that its Quantitative Easing, money printing/bond-buying binge would not only cease, but it would be reversed. We need no special predictive powers to raise doubt about Mr. Powell’s back-in-the-toolbox assurances. We need only recognize that stock and bond markets will surely view the 2020 largesse as a new routine, not a one-off maneuver. In recent years, we have already seen how the stock market pouts when the Fed ignores liquidity demands and disappoints its expectations.

While it is entirely logical to forecast future creations of fresh rescue money, we need to probe the depth of that well. To be sure, the mouth of the well is guarded by an Inflexible Principle:

Newly created units of fiat currency can only succeed when creditors who accept them as payment believe their value equals that of “old money” units.

A number of fiat currencies have run amok of that proposition, the most renowned of which was nearly 100 years ago, when an infamous wheelbarrow load of paper German Marks was needed to pay for ordinary household purchases. That German “money death” was not only shocking, it developed within months, despite government’s inevitable stop-gap actions.

WHAT SPOOKED THE FED? Fearing widespread Covid infection, hospitalization and death, state and local governments shut down nearly all human physical interaction in March this year. The stock market, having no way to assess and price the damage or its longevity, collapsed. Meanwhile, the Fed’s apparent fear was fear itself. A broad measure of investor fear can be gauged by the money market (despite its zero rate of return). US money market fund assets had been stable, around $3 trillion, until 2019 when they slowly climbed to $4 trillion. This year’s Covid shutdown and stock market plunge produced a money market spike to a sustained level above $5 trillion. That cash hoard is equal to about 23% of last year’s $22 trillion GDP. The Fed reacted by dumping out its toolbox of stimulants (details above).

US Money Market Assets (monthly)

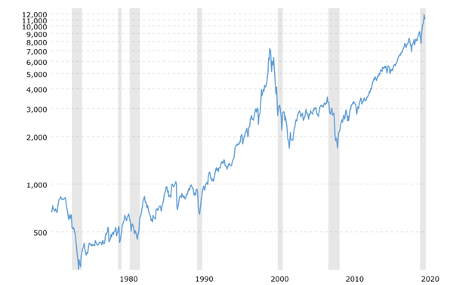

Tech Stocks: Have We Been Here Before?

Very few stock market mavens take note of the BBD, and those who do, do not seem to care. The US stock market in 2020 (think NASDAQ) has been melting upward, a la 1998-99. The Fed’s new policy, outlined above, is clearly designed to deliver maximum monetary stimulation to the economy. It will push us away from cash into riskier investments, primarily real estate, common stocks, junk bonds and various illiquid schemes. High quality bonds now pay nearly nothing. Indeed, if cash begins to charge depositors a negative rate of return, there will be no basis for anyone to hold it.

As is always the case, this time is different, say the mavens. At least today’s underpinnings are, in fact, different. In 1998-99, fledgling dot-com companies scrambled billions of nest-egg dollars. All dot-coms were considered to be technology companies, apparently because their products made use of the Internet. But, besides having lots of IPO money in their pockets, those companies often had slim human resources and a chronic shortage of management experience. By contrast, the 2020 tech companies that are now trading up within a bubble of high-altitude earnings multiples have viable, profitable businesses. This time, unlike 2000-02, if tech companies’ stocks do crash, the damage can only go so far, before most of them would become “fallen angel” value-type stocks. Current bubble-pricing of their shares can be evaluated from a capital scale-ability perspective. Microsoft’s business, for example, is now and always has been efficiently scalable. Amazon Web Services (cloud) is also very scalable, but Amazon’s core retail business is not, because its growth requires major additional physical plant and transportation investment, plus huge payroll expansion and training resources.

Amid the 2020 tech-stock runup, Tesla shares rose 500%, including the March dip. Forecasts of $6,000 share valuations (before its 5-for-1 split) and a gaggle of excited home-confined millennial day traders using the Robinhood platform, carried Tesla shares to incredible daily valuation changes.

While 2020 has thus far been the “Year of the NASDAQ” stock index, its history saw it plummet 76%, from its all-time high of 7,200 in February 2000, to 1,685 in September 2002. It hit that same low mark again in the Great Recession that ended in February 2009, but it took nearly 9 years to reach its 7,200 high again, in November 2017. But, in the past 3 years, it rocketed another 64%, to 11,787, just 2 months ago.

NASDAQ Index

APPENDIX: The Federal Reserve and the US Dollar; How We Got Here

The Federal Reserve became independent from the US Treasury in 1951, when it began following a deliberate policy to smooth and offset inflationary cycles, economic recessions and boom periods. That policy worked, for a time. The Fed implemented policy by way of buying and selling short term US Treasury bills in the open market. Via those market transactions, the Fed manipulated the money supply…. When it bought T-bills, new dollars were created by way of credits issued to the banking system, which in turn lent them to customers who spent them; and so the economy expanded. When the Fed sold T-bill investments, those dollars were removed from banks which lent less and the economy cooled (typically, in order to put the brakes on inflation).

The Fed’s money policy changed dramatically in the 1960s, when it began following an activist stabilization policy, shifting its priorities away from its inflation-smothering goal toward promoting high employment. The pro-growth shift produced a dramatic buildup of inflationary pressures from the late 1960s until 1979, when the new Fed chairman, Paul Volker vowed to choke off double-digit inflation and also pull the rug from a rapidly spreading number of “gold bug” speculators. He successfully did so, via a fast sequence of interest rate hikes that, in March 1980, touched a shocking, historic 20% high. It took the next 20 years for the Fed to ratchet down both its policy interest rate and the long-term bond market’s intractable fear of lurking inflation pressures.

A dollar’s value is always one dollar, but….

The US and other advanced countries were part of the “Bretton Woods System”, under which the US pegged the dollar to a $35 ounce of gold; by agreement, other countries pegged their currencies to the fixed-price, gold-locked US dollar. The dollar-link to gold, as expected, helped keep inflation low. And the dollar’s value was seldom discussed. Gold’s arbitrarily fixed value was incredibly naïve, though it was made to appear otherwise by a US law that, during the 41 years from 1933 to 1974, forbade US citizens from owning gold bars, coins and certificates. In 1971, President Nixon decreed that foreigners could no longer exchange their dollars for US Government-owned gold (at $35/ounce). The immediate effect: gold became market-priced and it never again visited the $35 neighborhood. Three years later, the US Congress repealed the legal ban on private ownership of gold. Thus, only 46 years ago, the gold-pegged/fixed valuation scheme that was hatched by 44 Allied nations in 1944, at Bretton Woods NH, was immediately obsolete; the US Dollar and all of its kindred-pegged network of currencies became “fiat money”…. government-decreed units of “legal tender” for settling public and private debts, with zero reference to any value per unit. Currency value was thereafter priced, on any given day, via currency exchange transactions made in open markets.

Meanwhile, gold is constant. It is one of 94 chemical elements that cannot be broken down or subdivided; it neither generates internal growth nor pays external dividends. And yet, gold’s value, in dollars, has multiplied 57x, from $35 to almost $2,000 per ounce (almost 8.5% compound annual magnification rate). The illustrative price-vs-value story goes like this: 50 years ago, a one-ounce gold coin would buy you a fine, tailor-made suit; in 2020, the price of that suit is still approximately one gold ounce. The story doesn’t prove that gold’s value has inflated; instead, it demonstrates that the US Dollar…. The $35 yardstick value, back in 1970…. has shrunk to 61 cents.

And now, cryptos

During the most recent 10 years, we have seen the introduction of global computer based, crypto-currencies that are neither created, controlled, nor accounted for by any government(s), or human coalitions; when used for payments, they record anonymous transactions. In order to assure constancy, the global quantity of cryptos is fixed, allegedly forever. Their value is not pegged to anything, such as fiat currency(ies), or precious metals. Investments in e-currencies do have dollar-priced market values, which fluctuate daily, in the open market, so that goods and services priced in dollars will require payment of less (or more) crypto-currency units.

The Endpoint? A universally available electronic yardstick to measure the changes in value of every fiat currency.

Commentary

Commentary was prepared for clients and prospective clients of FiduciaryVest LLC. It may not be suitable for others, and should not be disseminated without written permission. FiduciaryVest does not make any representation or warranties as to the accuracy or merit of the discussion, analysis, or opinions contained in commentaries as a basis for investment decision making. Any comments or general market related observations are based on information available at the time of writing, are for informational purposes only, are not intended as individual or specific advice, may not represent the opinions of the entire firm and should not be relied upon as a basis for making investment decisions.

All information contained herein is believed to be correct, though complete accuracy cannot be guaranteed. This information is subject to change without notice as market conditions change, will not be updated for subsequent events or changes in facts or opinion, and is not intended to predict the performance of any manager, individual security, currency, market sector, or portfolio.

This information may concur or may conflict with activities of any clients’ underlying portfolio managers or with actions taken by individual clients or clients collectively of FiduciaryVest for a variety of reasons, including but not limited to differences between and among their investment objectives. Investors are advised to consult with their investment professional about their specific financial needs and goals before making any investment decisions.

Investment Risk

FiduciaryVest does not represent, warrant, or imply that the services or methods of analysis employed can or will predict future results, successfully identify market tops or bottoms, or insulate client portfolios from losses due to market corrections or declines. Investment risks involve but are not limited to the following: systematic risk, interest rate risk, inflation risk, currency risk, liquidity risk, geopolitical risk, management risk, and credit risk. In addition to general risks associated with investing, certain products also pose additional risks. This and other important information is contained in the product prospectus or offering materials.